Last week we looked at an overview of the first Creation Story in Genesis 1:1-2:4a (the second Creation Story is in Genesis 2:4b-25). I think our discussion was extraordinary. This week we will be looking at the first three words of the Hebrew Scriptures: Bereshit bara Elohim (“In the beginning, God created” or literally “In the beginning created God”). This opening phrase raises innumerable avenues of thinking about and contemplating the nature of God. When we look at the first word “bereshit” or “beginning” two primary questions are raised. First, what is time’s relationship to God if God precedes the beginning? The second question is what occurred prior to the beginning?

Time:

In its entry on Eternity, the Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (“SEP”) begins its discussion with the observation that “a conception of how God relates to time is a defining element of any conception of God.” Whether we understand God to be outside of time or within time will necessarily influence everything else we say about God. If you would like to dive very deep into this issue from a modern perspective, I would recommend the SEP article or a shorter version from Eclectic Orthodoxy HERE.

In the latter third of the Confessions, St. Augustine (354-430) spends most of his time discussing and contemplating this first verse of Genesis. While ruminating on the word “Beginning”, he comes to the conclusion that time is a property of the created order and that therefore God is not subject to time. Time was created just like everything else. I have attached excerpts (Ch. XII-XXVI) from Book 11 of the Confessions. If you have time, please read through these excerpts. In my spiritual walk, this chapter is one of the most meaningful and significant readings that I have ever encountered. In chapter 3 of Book 4 of Mere Christianity entitled “Time and Beyond Time”, C.S. Lewis spends a few pages discussing this issue as well. Again, if you have time, please read Lewis. Lewis is easier to read than Augustine.

The Scriptures support this understanding of the atemporality of God. At Mt. Sinai, God discloses himself to Moses as “I AM WHO I AM.” Ex. 3:14. God’s essential nature is the eternal present. Likewise, in Revelation, God says “I am the Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end.” Rev. 22:13. He doesn’t say that he was the Alpha and will be the Omega, but that he is.

For next Tuesday, please spend some time thinking about the implications that time is part of creation and that God is outside of time. For me, the concept of God outside of time raises three broad issues: God’s impassibility, God’s foreknowledge, and our prayers.

The Impassibility of God:

In Christian thought, a basic idea is that God is immutable (unchanging) and impassible (not subject to emotion). These two characteristics of God arise out of God being outside of time. We say that God is unchangeable and is the same yesterday, today, and tomorrow, because yesterday, today, and tomorrow are all currently contemporaneously present in God right now. If we think of a timeline stretching from the Big Bang to the Second Coming – God contains the whole timeline and exists within his current state at every point on that timeline. When we ascribe human emotions to God, then we are saying that God changes – he was angry in the past, but now he is not. If God is outside of time, then this ascription is nonsensical. In classical Christian thought, therefore, when we ascribe an emotion to God, what we are really describing is our perception of our relationship with God, not God’s actual existing nature. For example, God only appears angry when we separate ourselves from him and are moving away from him.

Foreknowledge of God:

The second issue is that of God’s foreknowledge. All moments are presently present in God. If this is true, then do we have free will? If God knows what you are going to do tomorrow because tomorrow already exists in God, can you rightfully be said to have chosen to do that action? In the excerpt from “Mere Christianity”, C.S. Lewis says that God “does not ‘foresee’ you doing things tomorrow; He simply sees you doing them: because, though tomorrow is not yet there for you, it is for Him. You never supposed that your actions at this moment were any less free because God knows what you are doing. Well, He knows your tomorrow’s actions in just the same way — because He is already in tomorrow and can simply watch you. In a sense, He does not know your action till you have done it: but then the moment at which you have done it is already ‘Now’ for Him.”

For me, God’s atemporality and foreknowledge can be a source of great comfort. God is already there in our future. Regardless of the choices we make or the paths we take, God is there right now. Therefore, we can live into Jesus’ teaching of not being anxious about tomorrow because God already knows what tomorrow holds because God is already there with us. Matt. 6:34

Timelessness of God in Prayer:

The third issue that arises for me in understanding God as being outside of Time is within my prayer life. We believe that prayer is effective beyond geography. We believe that our prayers for the victims of Australia’s fires are efficacious. However, since the God to whom we pray is outside of time, our prayers are also not limited to the present. We can pray for those in the past or those in the future just as easily as we pray for those who are not physically with us. On a personal level, whenever I watch a war movie (Saving Private Ryan, Gettysburg, Glory, Henry V, etc.), I find myself praying for the actual men in the events being represented. Although we know the outcome of the events, nonetheless, these men are fearful, injured, and dying. They could use our prayers. Several years ago, we visited the Nazi pillboxes on Pointe du Hoc. As I looked over the Normandy coast into the English Channel, I had the overwhelming urge to pray for both the men in the pillboxes who knew they would probably not see another sunrise and for those men in the boats coming to climb the cliffs. I think my prayers that day for those men were effective.

Also, within our prayer life, the timelessness of God impacts my understanding of the Eucharist. At the instant in which I take communion, I, like every other Christian, am joined with God. Therefore, at the time I take communion, I am joined with everyone who has ever participated in communion or who will ever participate in communion from the Last Supper in the upper room to the marriage supper of the lamb in Revelation (Rev. 19:9). At that moment, the communion of saints presently and fully exists, because God presently and fully exists to all Christians at all times at the same time.

The Pre-Existence of God:

The question arises, what happened before creation? In chapter XII of Book 11 of “The Confessions”, St. Augustine writes that some of his contemporaries answer that question by saying “He was preparing Hell for those who pry too deep.” Augustine says that the appropriate response to the question is “I do not know what I do not know.” In his later work, The City of God, (Book 11, Ch.6), St. Augustine reasons that because motion and change must succeed one another and cannot occur simultaneously, the question is utter nonsense. God cannot properly be said to have done anything prior to creation, because doing implies temporality. Since time is a property of creation, then no action could have taken place prior to time’s creation. (This is the same argument used by modern theoretical physicists. Time was created by the Big Bang, and therefore nothing can properly be said to have occurred prior to the Big Bang. A short discussion by Stephen Hawking is HERE.) Nothing can “happen” until time is created.

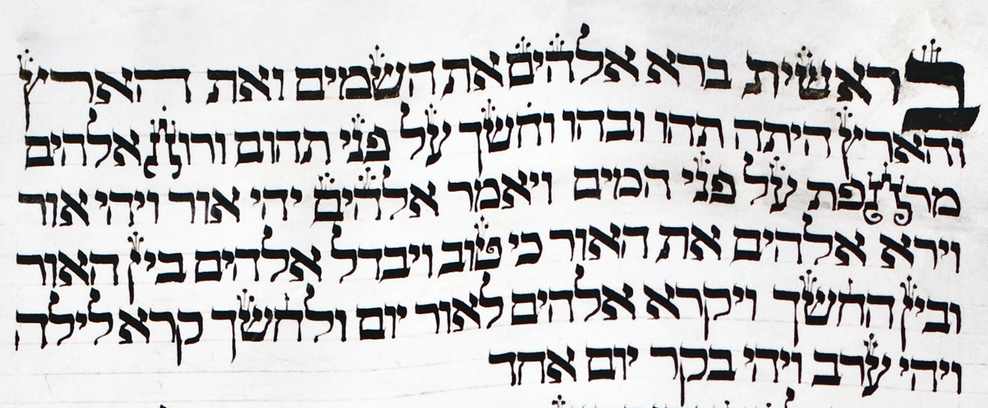

Jewish thought has a better explanation that goes back to the first letter of the Scriptures. The question posed was why did God chose to begin the Scriptures with the second letter of the alphabet, bet (corresponding to our letter “B”) and not the first letter of the alphabet, aleph (corresponding to our letter “A”). The answer lies in the shape of the letter. Hebrew is read right to left, and bet is a three-sided rectangle with the right side, top, and bottom closed. The left side (the side opened to the remainder of Scripture) is opened. In looking at the above picture of the first two verses of Genesis, notice how “bet” frames the Scriptures like a bracket.

As recorded in the Bereshit Rabbah the answer is that “just as a bet is closed on all sides and open in the front, so you are not permitted to say, ‘What is beneath? What is above? What came before? What will come after?’ Rather only from the day the world was created and after. Bar Kappara said: ‘You have but to inquire about bygone ages that came before you’ (Deut. 4:32). From the moment God created them you may speculate, however, you may not speculate on what was before that.” Book I, ch 10.

In the Kabbalah system of Jewish thought, with the shape of the letter bet, the roof says you cannot perceive what is beyond our world, the floor below so you cannot fall out of the world, and the wall behind says you cannot know what came before you, but because there is no wall in front, then the bet does not hold the future for you. A ninety-second cartoon explaining bet is HERE.

What, then, is time? If no one asks me, I know what it is. If I wish to explain it to him who asks me, I do not know.

St. Augustine, Confessions, 11.14.17

Pingback: Everywhere Present – Week 4(a) – The Hallway at the End of the World – Ancient Anglican

Pingback: The Revelation – The Vision of God – Rev. 4 – Ancient Anglican

Pingback: The Revelation – Washed in the Blood – Rev. 7 – Ancient Anglican

Pingback: Prayer in the Night – Keep Watch, Dear Lord: Pain and Presence, pt.2 – Ancient Anglican