In this study we read through Richard Beck’s book Trains, Jesus, and Murder – The Gospel According to Johnny Cash. The book grew out of a bible study Beck leads at a local maximum-security prison. In the book, Beck shows us how Cash, like Jesus, brings us into the presence of the marginalized and forgotten people of our society – the imprisoned, the heartbroken, the beaten down, Native Americans, common laborers, drug addicts, and those who have never felt the love of Jesus. For the men that Cash sang to and about or the men that Beck leads in bible study, sin and its consequences and the promise of one day being free are not theoretical ideas to be discussed, but an ever-present reality that is lived. In many ways, Cash’s songs are a psalmody for our time. This Epiphany Lesson covers seven weeks.

(Epiphany 2021)

The Gospel According to Johnny Cash

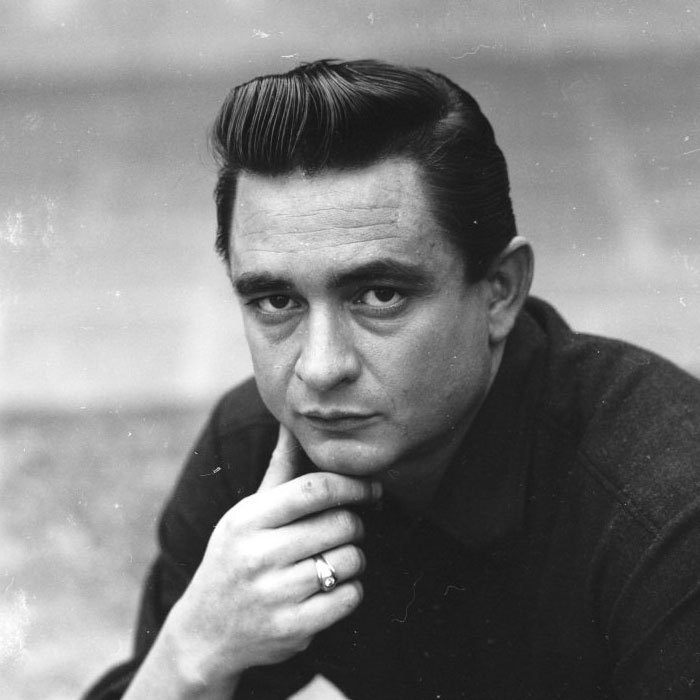

The gospel according to the Man in Black is a gospel rooted in solidarity. The cross of Christ is an act of divine identification with the oppressed, the cursed, and the godforesaken.

The bank of the Jordan, on this side of the Resurrection, is full of life’s storms – heartbreak, regret, failure, and death – but we can see the other side. We can see that fair and happy land. Will you come and go with me.

The Good News of Jesus Christ, however, is that our salvation lies not in our walking-the-line for God, but in God, through Christ, walking-the-line for us.

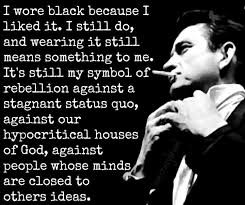

“The Man in Black” not only identifies Cash with the outcast but it calls us to do so as well. Solidarity requires that we be found among the forgotten, because that is where we find Jesus. Solidarity implies that we be involved just as he was.

In the parable, Jesus is not the do-gooding sheep who goes out to the disenfranchised, rather Jesus IS the disenfranchised. In the live version of the song, Cash introduces us to Jesus in the voices of the prisoners that we hear.

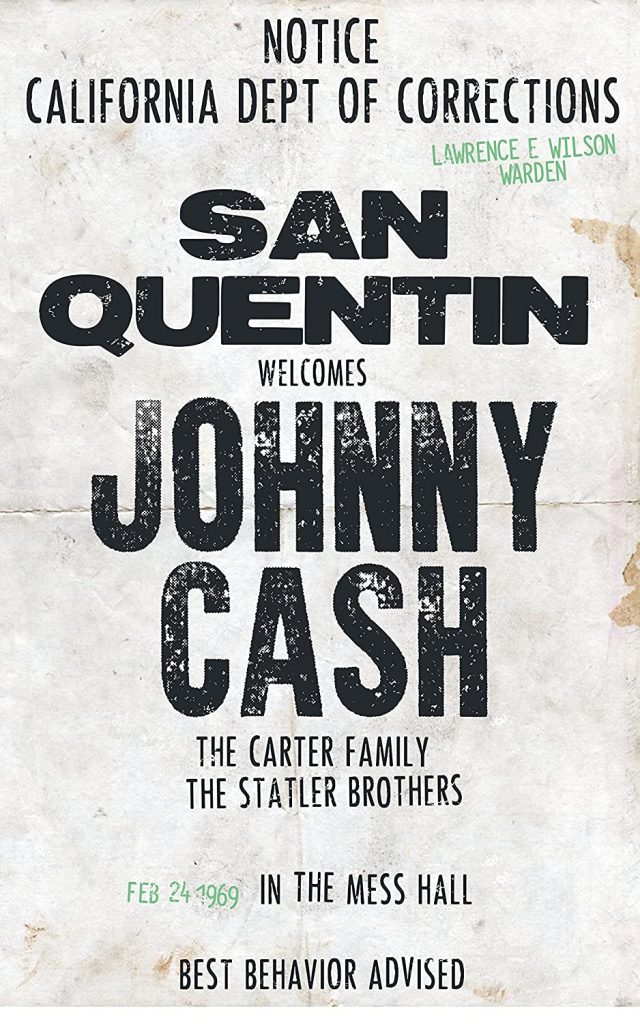

The song uses the physical presence of Greystone Chapel as a metaphor for the vibrant spirituality that can be found within prison when a person’s mind who is aligned with Jesus can transcend his physical circumstances. For “where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom.” 2 Cor. 3:17.

Cash plays the role of the prophet. He sings about the dehumanization, brutality, and ultimate ineffectiveness of San Quentin Prison. His hatred for the institution pervades the entire song. Cash knows that he is singing for those who have no voice for the injustices that they face.

God is always found on the side of the oppressed, not because they are inherently better than the oppressor, but rather simply because they are oppressed. The challenge for us is to see the world as God sees the world.

We are called to be neighbors to those in need in a personal, concrete, and intimate way. Our prayer should be that Christ will open our eyes to see those opportunities to be a neighbor like the traveler in the song.

What Jesus requires of us, is to see the dignity of everyone, not simply as the cog in the means of production, and to walk in solidarity with them. The problems that face working men and women today of which Cash sings are still with us today.

“Sunday Morning Coming Down” is our reality into which the good news of Jesus Christ is spoken. The story of the Gospel begins with the recognition that we are enslaved to the elemental spirits of this world. (Gal. 4:1-9).

Our love of God must be primary. Everything in our lives, including our love of country, but be subservient to our love of God and must be properly ordered in light of the teachings of Jesus. Our citizenship of our country can never take priority over our citizenship in heaven.

It is only those who have neither fired a shot nor heard the shrieks and groans of the wounded who cry aloud for blood, more vengeance, more desolation. War is hell.

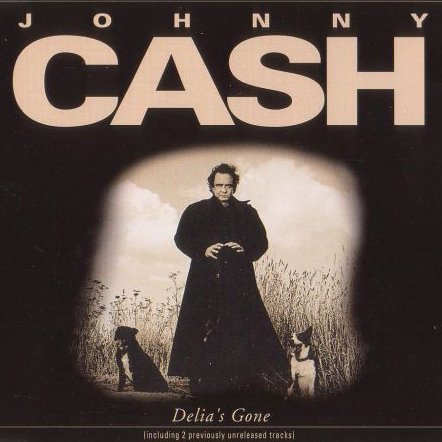

The gospel message in “Delia’s Gone” is that the sin is its own punishment. The man doesn’t need to wait on the civil authorities or God himself to mete out retribution, the punishment flows from the act itself.

The story ends with Cash singing with weakness and humility. It ends with God’s grace being perfected within him. It ends with him having solidarity with Jesus.