Finding the God Who is Love

Posted on 11 March 2019 by Fr Aidan Kimel

The love of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit for human beings is absolute and unconditional. This fundamental truth of the gospel bears repeating. It bears repeating because we Christians seem to forget it all too easily. We know the evangelical words of our faith—

- “God is love”

- “Christ died for the ungodly”

- “There is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus”

- “This is my body which is broken for you”

- “Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof, but only say the word and my soul shall be healed”

- “We have seen the True Light; we have received the Heavenly Spirit; we have found the True Faith, worshiping the Undivided Trinity, who has saved us”

—and we can recite from heart the parable of the prodigal son and the stories of Jesus and the paralytic and the woman caught in adultery. Yet we seem to prefer a different, more oppressive narrative. It goes something like this:

Because we sin and repeatedly sin, God is angry with us. But if we repent of our sins, he will change his attitude, restore fellowship, and bring us into heaven, if we persevere and die in a state of grace.

Orthodox, Catholics, and Protestants tell different versions of the story, but the narrative remains constant: God is a God of conditional love. If we fulfill specific conditions, God will be to us loving and merciful; if not, wrathful and punishing. God is Dr Jekyll or Mr Hyde. Which one we meet depends on our performance.

And so I reiterate: the love of God for human beings is absolute and unconditional. God does not love us because of anything we have done. He does not love us because we are virtuous or obedient or kind; nor does he cease to love us when we disobey his commandments and fail to love as we should. He does not cease to love even when we commit evil. God’s love for us is unmerited, unqualified, unreserved, immutable, infinite. We cannot earn it, no matter how hard we try; we cannot lose it, no matter how hard we try. He does not change his mind. The Father of Jesus Christ is eternally and hopelessly in love with the creatures he made in his image.

The Dominican theologian, Fr Herbert McCabe, rejoiced in the unconditional love of God and found it curious that Christians would want to believe in a deity of wrath and retribution:

It is very odd that people should think that when we do good God will reward us and when we do evil he will punish us. I mean it is very odd that Christians should think this, that God deals out to us what we deserve. It is not, I suppose, really odd that other people should; I suppose it is the commonest way of thinking of God, for God tends to be just a great projection into the sky of our moral feelings, especially our gut feelings. But I don’t believe in God if that’s what he is, and it is very odd that any Christian should, since there is so much in the gospels to tell us differently. You could say that the main theme of the preaching of Jesus is that God isn’t like that at all. (“Forgiveness,” Faith Within Reason, p. 155)

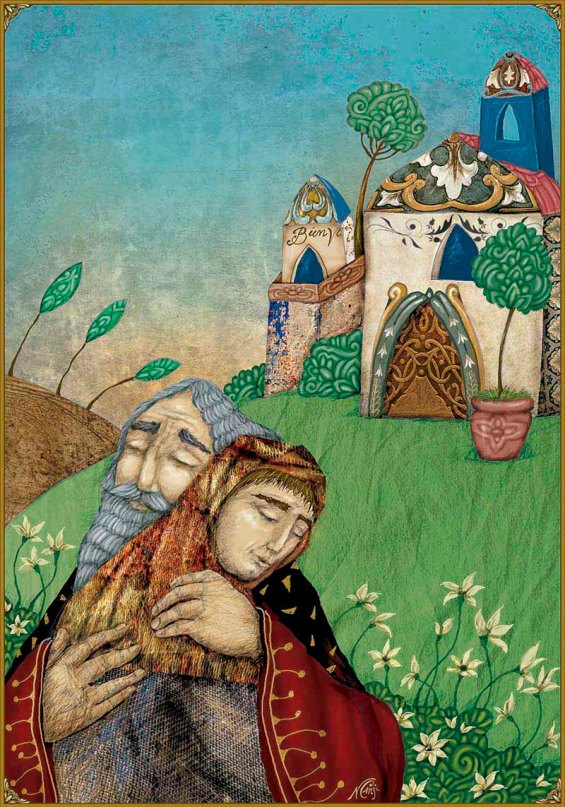

Recall the parable of the prodigal son (Luke 15: 11-32). The younger son takes his inheritance and squanders it in a far country. Eventually he finds himself hungry and destitute, pigs his only company. In despair he acknowledges to himself, and later to his father, how his sin has altered his relationship with his father: “I am no longer worthy to be called your son; treat me as one of your hired servants.” But what precisely has changed? Has the father ceased to love his son? Has he become the angry patriarch the prodigal now fears him to be? On the contrary, the father has been waiting for his son to return, and upon seeing him in the distance, he jubilantly rushes to greet him and welcome him home. The father has not changed in his love for his son. What has changed is the son. In his alienation and guilt, the prodigal is no longer capable of seeing his father as he really is. He has created his own alternate reality. Instead of a parent abounding in love and care, he has substituted an overseer of exacting justice. The best he can now hope for is that this wealthy man might have pity upon him and take him on as one of his servants. And so it is in our relationship with God:

Sin is something that changes God into a projection of our guilt, so that we don’t see the real God at all; all we see is some kind of judge. God (the whole meaning and purpose and point of our existence) has become a condemnation of us. God has been turned into Satan, the accuser of man, the paymaster, the one who weighs our deeds and condemns us. (pp. 155-156)

The father does not need to be persuaded to forgive and welcome his son. He does not need to be cajoled or appeased. He does not need to change his mind. He loves his son. Period. That is his truth. All the son needs to do is to see his sin for what it is and acknowledge himself as a sinner—and at that moment he ceases to be one. His contrition is the divine forgiveness. All the rest is celebration and feasting: “This is all the real God ever does, because God, the real God, is just helplessly and hopelessly in love with us. He is unconditionally in love with us” (p. 156).

God doesn’t change his mind about us, McCabe declares; God changes our mind about him—again and again and again. McCabe is direct and pointed:

His love for us doesn’t depend on what we do or what we are like. He doesn’t care whether we are sinners or not. It makes no difference to him. He is just waiting to welcome us with joy and love. Sin doesn’t alter God’s attitude to us; it alters our attitude to him, so that we change him from the God who is simply love and nothing else, into this punitive ogre, this Satan. Sin matters enormously to us if we are sinners; it doesn’t matter at all to God. In a fairly literal sense he doesn’t give a damn about our sin. It is we who give the damns. We damn ourselves because we would rather justify ourselves, than be taken out of ourselves by the infinite love of God. (p. 157)

I was more than a tad shocked when I first read these words. How can our sin not make a difference to God? If we could ask McCabe this question, I think he would first remind us precisely who and what God is. God is not a being within the continuum of the cosmos. He is not a part of the world. He is not a god. He is the infinite plenitude of Being who surpasses the world he has made. The world makes no literal difference to God. This is what we mean when we speak of the divine aseity, and this is what we mean when we declare that the transcendent Deity created the world from out of nothing. He did not have to create the universe. If he had chosen not to, his glory would not have been diminished one whit, nor is he happier because he did do so. God plus the world is not greater than God alone. The world does not add anything to the Creator; it does not change or affect him. The mutuality that marks beings within the world does not characterize God’s relationship with beings. Ultimately the world cannot make a difference to God. God is God, and we are the finite manifestations of his love. Robert Sokolowski describes this as the “Christian distinction”:

In the distinctions that occur normally within the setting of the world, each term distinguished is what it is precisely by not being that which it is distinguishable from. Its being is established partially by its otherness, and therefore its being depends on its distinction from others. But in the Christian distinction God is understood as “being” God entirely apart from any relation of otherness to the world or to the whole. God could and would be God even if there were no world. Thus the Christian distinction is appreciated as a distinction that did not have to be, even though it in fact is. The most fundamental thing we come to in Christianity, the distinction between the world and God, is appreciated as not being the most fundamental thing after all, because one of the terms of the distinction, God, is more fundamental than the distinction itself. (The God of Faith and Reason, pp. 32-33)

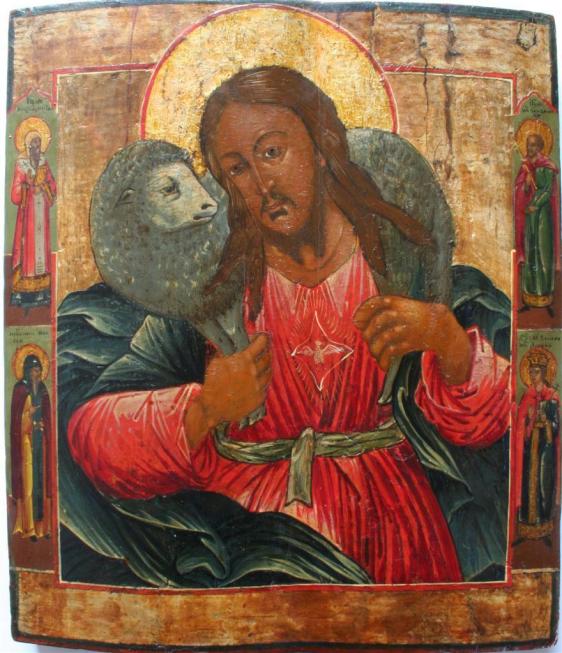

God is more fundamental than the distinction between Creator and creature. Whereas beings are defined by their relations with other beings, such does not obtain between God and the world. Beings stand alongside each other and interact with each other; they share a world together; but none of this obtains with God and beings. As McCabe states: “God cannot share a world with us–if he did he would have created himself. God cannot be outside, or alongside, what he has made. Everything only exists by being constantly held in being by him” (“Freedom,” God Matters, p. 14). God is outpouring Love who sustains, upholds, indwells all that is. In him we live and move and have our being. Again McCabe: “God is the ultimate depth of our beings making us to be ourselves” (“The Trinity and Prayer,” God Still Matters, p. 59)

Once we understand the Christian distinction between divinity and the world, we are positioned to discern the limitations and anthropomorphism of the biblical stories we tell about God. Stories we must tell, for God presents himself to us by story, as story–yet the figurative nature of these stories must be recognized, if the Christian distinction is to be respected.

Christians proclaim the forgiveness of God; but what precisely do we mean when we say that God forgives us? In human relations we forgive someone who has offended us. Offense is something deeper than injury. If someone injures us accidentally, we may deserve compensation but we do not require an apology. But if someone offends us, if someone attacks us or harms those we love, then apology, and perhaps much more than apology, is needed. Atonement must be made, restitution provided. Still one thing more is needed, though, if fellowship is to be restored: the injured party must surrender his right to vengeance. He must forgive. Only thus can both offender and offended be healed and recreated.

The language of offense, atonement, and forgiveness has been appropriately transferred to the relations between God and man. “O my God, I am heartily sorry for having offended Thee, and I detest all my sins, because I dread the loss of heaven, and the pains of hell; but most of all because they offend Thee, my God, Who are all good and deserving of all my love”—so begins a traditional Latin form of the act of contrition. Similarly, a preparatory prayer for communion composed by St John Chrysostom begins: “O Lord my God, I know that I am not worthy nor sufficiently pleasing that Thou shouldst come under the roof of the house of my soul, for it is entirely desolate and fallen in ruin.” It is vitally important for us to speak words like this to God; but it is equally important to recognize their figurative intent and limits:

God, of course, is not injured or insulted or threatened by our sin. So, when we speak of him forgiving, we are using the word “forgiving” in a rather stretched way, a rather far-fetched way. We speak of God forgiving not because he is really offended but accepts our apology or agrees to overlook the insult. What God is doing is like forgiveness not because of anything that happens in God, but because of what happens in us, because of the re-creative and redemptive side of forgiveness. All the insult and injury we do in sinning is to ourselves alone, not to God. We speak of God forgiving us because he comes to us to save us from ourselves, to restore us after we have injured ourselves, to redeem and re-create us.

We can forgive enemies even though they do not apologize and are not contrite. But such forgiveness … does not help them, does not re-create them. In such forgiveness we are changed, we change from being vengeful to being forgiving, but our enemy does not change. When it comes to God, however, it would make no sense to say he forgives the sinner without the sinner being contrite. For God’s forgiveness just means the change he brings about in the sinner, the sorrow and repentance he gives to the sinner. God’s forgiveness does not mean that God changes from being vengeful to being forgiving, God’s forgiveness does not mean any change whatever in God. It just means the change in the sinner that God’s unwavering and eternal love brings about … Our repentance is God’s forgiveness of us. (God, Christ and Us, pp. 121-122)

The language of faith is filled with conflicting images of God—the image of the wrathful God who hates our sin and requires propitiation; the image of the God who endures our iniquities, who is long-suffering and abounding in mercy; the God who punishes the wicked and forgives the penitent. These conflicting images are helpful, necessary, and unavoidable. But it is also necessary, says McCabe, for us to think clearly:

The initiative is always with God. When God forgives our sin, he is not changing his mind about us; he is changing our mind about him. He does not change; his mind is never anything but loving; he is love. The forgiveness of God is God’s creative and re-creative love making the desert bloom again, bringing us back from dry sterility to the rich luxuriant life bursting out all over the place. When God changes your mind in this way, when he pours out on you his Spirit of new life, it is exhilarating, but it is also fairly painful. There is a trauma of rebirth as perhaps there is of birth. The exhilaration and the pain that belong to being reborn is what we call contrition, and this is the forgiveness of sin. Contrition is not anxious guilt about sin; it is the continual recognition in hope that the Spirit has come to me as healing my sin.

So it is not literally true that because we are sorry God decides to forgive us. That is a perfectly good story, but it is only a story. The literal truth is that we are sorry because God forgives us. Our sorrow for sin just is the forgiveness of God working within us. Contrition and forgiveness are just two names for the same thing, they are the gift of the Holy Spirit; the re-creative transforming act of God in us. God does not forgive us because of anything he finds in us; he forgives us out of his sheer delight, his exuberant joy in making the desert bloom. (pp. 16-17)

McCabe’s emphasis on the priority of grace may strike some Orthodox readers as too Augustinian. What about synergism? Do we not still have to cooperate with God? And of course this is true. But too often the popular understanding of synergism forgets the divine transcendence and reduces God to a being within the world, as if God does the hard work, dragging us 90% of the way up the hill of salvation, but then drops us and leaves us to climb the rest of the way ourselves. God does his part, but now it’s up to us to do ours—repentance is our autonomous work. But God is not a thing alongside us. He is our Creator and the transcendent source of our being and freedom. Divine grace does not compete with creaturely agency. As Met Kallistos Ware observes, “the inter-relationship between divine grace and human freedom remains always a mystery beyond our comprehension” (How Are We Saved?, p. 36). Faith is a gift and therefore always a surprise. In the midst of spiritual death we miraculously discover within ourselves the ability to call upon the Savior: “Lord, have mercy upon me, a sinner!” As St John Cassian writes, “He puts into us the very beginnings of salvation” (Conf 13.18). We understandably think of divine absolution as occuring after we have confessed our sins and done our works of penance, yet the reverse is the literal truth. God takes the initiative in everything. The faith and repentance that restores us to our Father just is his forgiveness of our sins. “At every point,” Ware explains, “our human cooperation is itself the work of the Holy Spirit” (p. 43).

The God of the gospel is not the Jekyll and Hyde of our nightmares. He is not a God we need to appease. He is not a God we need to persuade to forgive. He is not a God who puts conditions on his mercy and care. He is, rather, the Father who hurries to us in love, only in love, relentlessly and passionately in love. We search for the God who is Love, yet in truth he has already found us and prepared the banquet of salvation.