Sing to the Lord a new song, for he has done marvelous things.

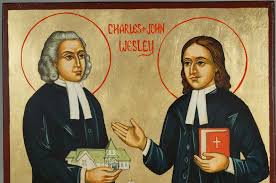

Today we celebrate the ministry of John and Charles Wesley. If my wife had had no objection, our son would have been named Charles Wesley Jordan. Having grown up Methodist, these two men hold a special place for me.

The year is 1400 in Prague in the Kingdom of Bohemia. One hundred years before the Protestant reformation and 400 years before the birth of John and Charles Wesley, a young priest by the name of John Hus speaks out against the excesses of the medieval church. He writes hymns to be sung by his congregation to common melodies, unlike the polyphony chants of the cathedrals. Hus is burned at the stake, but his movement called the Moravians survive.

Fast-forward to the Church of England in the 18th Century. The church is under the influence of the Puritan Calvinist. Churches were generally austere with preaching based upon erudite biblical exegesis. The only hymns to be sung are those from the Scriptures. The Canticles of Morning and Evening Prayer such as the Song of Mary or Song of Simeon and the Psalms are set to music. Instrumental accompaniment is discouraged. The great Reformation hymns of Martin Luther and the melodies of J. S. Bach are generally unknown. Church attendance on Easter Sunday is about 10% of the population.

Into this time, two brothers, John and Charles Wesley are graduated from Oxford University and ordained priests in the Anglican Church. In 1735, they were sent to the colony of Georgia on a largely unsuccessful missionary endeavor.

On their return trip to England two years later, the ship carrying the brothers encountered a great storm. While others panicked, their Moravian shipmates sang the hymns of John Hus, Martin Luther, and others.

Upon their return to England, the brothers, still ordained clergy, began to attend a Moravian meeting house on Aldersgate Street in London. It was there that their hearts were “strangely warmed” and both brothers first knew the very presence of God – Father, Son, and Holy Spirit – in their lives.

Inspired by the Holy Spirit, John and Charles set out to the port city of Bristol for “the poor had yet the gospel preached unto them.” When the Lord asked: “Whom shall I send,” John and Charles answered the call “Send Me!”

John began to preach in the fields near the docks or the mines to those who had never darkened a church’s door. On a typical Sunday, John would hold upwards of ten services throughout the cities and villages of England, bringing the good news of Jesus Christ to those who had not heard. Each service would follow the Book of Common Prayer with Communion, but each would contain a robust preaching extolling the love and grace of God for all, and a robust singing to mirror the songs of the docks, and the mines, and the fields.

His brother Charles would come to publish almost 6,000 hymns, of which 21 are still retained in the 1979 hymnal including Lo, He Comes with Clouds Descending, Come thou Long Expected Jesus, Hark the Herald Angles Sing, Jesus Christ is Risen Today, O For a Thousand Tongues to Sing, and Love Divine All Love Excelling.

John’s preaching and Charles’s hymnody set off the Great Awakening in both England and America. They would attract thousands at a single service. And the Holy Spirit moved greatly through their preaching and their hymnody. Although the Church first rejected their methods as too enthusiastic, by the 19th century, their style of preaching and their hymns would come to be heard in almost all the churches of England. Although the Wesley Brothers founded the evangelical movement in Anglicanism, their emphasis on weekly communion and the hymns they sang would later inspire the Anglo-Catholic movement of the mid-19th century.

Ezekiel tells us of the valley of dry bones, and it is through the preaching of John and the hymns of Charles that a moribund church received a new song that breathed life back into these dry bones.

On the anniversary of his conversion experience, Charles wrote “O For a Thousand Tongues to Sing.” It is this hymn which best capture the work of John and Charles:

O For a thousand tongues to sing

My dear Redeemer’s praise!

The glories of my God and King,

The triumphs of His grace!

My gracious Master and my God,

Assist me to proclaim,

To spread through all the world abroad

The honors of Thy name.

Jesus! the Name that charms our fears,

That bids our sorrows cease;

‘Tis music in the sinner’s ears,

‘Tis life, and health, and peace.

Charles died in 1788 and John in 1791. Although the followers of the enthusiastic evangelicalism would create the Methodist Church in both England and America, both men remained Anglican clergy until their death.

Rules of Singing:

During his ministry, John Wesley published a list of seven directions for how to sing in Church. I want to conclude this meditation with these rules:

1. Learn the tunes of the hymns.

2. Sing the words exactly as they are printed here, without altering or mending them at all; and if you have learned to sing them otherwise, unlearn it as soon as you can.

3. Sing all. See that you join with the congregation as frequently as you can. Let not a slight degree of weakness or weariness hinder you. If it is a cross to you, take it up, and you will find it a blessing.

4. Sing lustily and with good courage. Beware of singing as if you were half dead, or half asleep, but lift up your voice with strength.

5. Sing modestly. Do not bawl, so as to be heard above or distinct from the rest of the congregation, that you may not destroy the harmony; but strive to unite your voices together, so as to make one clear melodious sound.

6. Sing in time. Whatever time is sung be sure to keep with it. Do not run before nor stay behind it, but attend close to the leading voices, and move therewith as exactly as you can, and take care not to sing too slow.

7. Above all sing spiritually. Have an eye to God in every word you sing. Aim at pleasing him more than yourself, or any other creature.

Pingback: Passion Predictions in John – Week 2 – John 3:12-21 – Ancient Anglican